With Napoléon encamped in Moscow in October 1812, waiting impatiently for terms of surrender, and with General Kutuzov and the Russian army hunkered down just fifty miles to the southwest, Russia’s thirty-five-year-old emperor, Tsar Alexander I, stared outside his St. Petersburg palace window, wondering what his next move should be. Stung by his staggering losses at Borodino, saddened by those who now called him a coward, and secretly tormenting himself for Russia’s steep decline, Tsar Alexander was a discouraged, almost defeated, man.

Equestrian Portrait of Alexander I (1777-1825), by Franz Krüger (c. 1837, Hermitage).

Equestrian Portrait of Alexander I (1777-1825), by Franz Krüger (c. 1837, Hermitage).

In this moment of despair, he once more reverted to studying the Holy Bible while listening intently to the counsel of his lifelong, boyhood friend Prince Alexander Golitzen, now procurator of the Holy Synod and effective leader of the Russian Orthodox Church. As the story goes, Golitzen was in the act of opening a huge, folio-sized Bible in front of Alexander when it suddenly slipped from his grasp, fell to the floor, and opened to the book of Psalms, the ninety-first chapter: “I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress, my God; in him will I trust. . . . He shall cover thee with his feathers and under his wings shalt thou trust: Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night; nor for the arrow that flieth by day. . . . A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee” (Psalm 91:2, 5, 7).

Upon hearing the same verse read at church the following day, Alexander took it as a heaven-sent sign and immediately plunged headlong into an intensive study of the Old Testament prophets. “I simply devoured the Bible,” he later admitted, “finding that its words poured an unknown peace into my heart and quenched the thirst of my soul.”[1] Feeling that Russia’s defeat was a personal condemnation for his past sins, Alexander gained a new level of inspiration and sense of forgiveness from searching the scriptures. He gained a resolve to continue the conflict against the conqueror. When the French emperor demanded terms, an emboldened Alexander thundered back his now famous retort, “Peace? We have not yet made war!”[2] As history has shown, Alexander, more than any other man, would become responsible for defeating the French and for the restructuring of the new European order.

So who was this enigma of St. Petersburg? Who were the ghosts that haunted him and the men and women who inspired him? What role did he eventually play in refashioning Europe after the end of the Napoleonic Wars? And what contributions would he make to the era of profound peace that followed the Congress of Vienna and that came to characterize the age of 1820, our continuing focal point of study?

“Something Is Missing in His Character”

Alexander was his grandmother’s son—or at least he seemed to be. Catherine the Great, who had wrested the empire from her husband in 1762, would rule Russia until 1796. A powerful, often ruthless, woman whose life was her country, Catherine expanded the Russian Empire by force of conquest to the Black Sea and the Crimea, transforming Russia into a true superpower. While expanding Russia’s vast and seemingly limitless borders, she initiated important liberalizing reforms that endeared her to her people, such as reducing the powers of the clergy, improving education at all levels, establishing a system of local governments, supporting the arts, and modernizing a country and society still slow and almost boorishly backward by modern European standards. She desperately sought to continue such liberal reforms and territorial expansions through her successor son, Paul, but concluded that by disposition and deportment, he would utterly fail her and the Empire. She disdained him for his pedantry, his lack of vision and intelligence, and instead fastened her attention on her grandsons, Alexander (born in 1777) and his younger brother, Constantine (born in 1779), both sons of Paul and his wife, Maria Feodorovna. With no law of primogeniture in place, it was the reigning Russian monarch’s right to choose his or her own successor.

Catherine came to favor Alexander as much as she disdained her own son. She saw in her grandson, who was indeed precocious, gifted, and startlingly handsome, the very qualities her son lacked, and she actively planned for Alexander to succeed her to the throne. Denying his parents of their rightful role, Catherine assumed the rearing and governorship of Alexander and resolved to mold him into the kind of leader she believed Russia needed in the coming nineteenth century.

Although Alexander was born in a palace, Catherine raised him in austere conditions so he would know the hardships of his people. His bedroom window would always be left open so that he would feel the cold of a Russian winter. His bed was never comfortable; it was one made of straw and thick leather. She purposely ordered regimental batteries nearby to fire their cannons and shout their orders so loudly that Alexander would easily hear them and sense early on the rhythm and sounds of military life. Because of this, he lost the hearing in his left ear in his early youth. On the other hand, she insisted that he wear the finest clothes and the best in silk stockings, that he be exposed to fine art and great literature, and that he learn to appreciate high society and the fineries of royalty and high court living.

Catherine II, by Franz Krüge, after Roslin (c. 1770, Hermitage).

Catherine II, by Franz Krüge, after Roslin (c. 1770, Hermitage).

After Alexander turned twelve years old, Catherine entrusted his education to the noted Swiss tutor Frédéric La Harpe. A liberal and republican by training and a friend of Rousseau, La Harpe emphasized the arts and the humanities over math and science and taught his young pupil in the principles of the Enlightenment, exposing him to such writers and thinkers as Plato, Demosthenes, Plutarch, Tacitus, Locke, and Descartes. If not a gifted student, Alexander soon gained “a comfortable command of five languages,” including English but especially French, the language of international diplomacy. Soon it became his favored language. Ironically, he was never able to communicate thoroughly in his native Russian. La Harpe’s influence upon Alexander was profound and contributed much to his developing sense of egalitarianism, needed liberal reforms, social justice, and careful diplomacy. Until La Harpe’s death in 1838, the two men carried on a warm and friendly correspondence, a godfather-godson type of relationship.

Catherine also selected the woman Alexander would marry. After searching everywhere in royal courts all across Europe, she finally settled on the young and beautiful fifteen-year-old German princess Louise of Baden—the Grand Duchess Elizaveta Alexeyovna, as she came to be called. Elizabeth was a charming and intelligent, though not forceful, woman. She and Alexander were married in a grand royal wedding ceremony in St. Petersburg on 28 September 1793 to the applause of thousands and the thundering peals of a twenty-one-gun salute.

Elizaveta Alexayovna. Portrait of Empress Elisabeth Alexeievna of Russia, by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1795, Castle of Wolfsgarten).

Elizaveta Alexayovna. Portrait of Empress Elisabeth Alexeievna of Russia, by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1795, Castle of Wolfsgarten).

Alexander had a romantic longing that he never satisfied in the marriage bed. He enjoyed being around beautiful and intelligent women “in whose company he found greater comfort than he ever did with men.” Scandalously unfaithful, he took on a succession of mistresses, his lifelong favorite being the beautiful and seductive Polish countess Maria Naryshkina (1779-1854), who bore him at least one daughter. As one scholar wryly noted, “Sex to him was a many-roomed mansion.”[3]

Arranged marriages seldom spoke of love and rarely succeeded, but the marriage of Alexander and Elizabeth came to be one of true friendship that deepened through the years. She gave birth to a daughter, Lisinka, who died when only eighteen months old, and never produced a male heir. Alexander, though not quite sixteen years of age when he married, was already smarting under the dominance of his demanding, overly controlling grandmother. Gradually he asserted his independence and reverted more and more to the influences of his own parents—his father teaching him a love for military drill, parade dress, and procession and his mother cultivating a sense of tenderness and dealing mercifully with others.

So the future emperor learned contrasting worlds—absolutism and brute force on the one hand, liberalism and a spirit of kind forgiveness on the other. He was, as the Russian romantic poet Aleksandr Pushkin once called him, “a Sphinx who carried his riddle with him to the tomb.”[4] A born diplomat, astute politician, and dramatist who knew how to handle people in virtually every situation, Alexander was inconsistent and secretive, as one who never really knew himself nor the full consequences of his actions. Said Napoléon, who Alexander ever admired as the greatest man of the age, “Something is missing in his character, but I find it impossible to discover what it is.”[5]

An Ambivalent Hamlet

But there was much more to Alexander’s troubled soul. With the unexpected death of Catherine the Great by a stroke in November 1796, her son Paul, the “mad tsar,” became emperor of Russia’s forty million people. Unprepared for leadership, poorly taught, and ill-disposed by personality and training to handle the rigors of a position his mother never believed he could fulfill, Paul proved a dismal failure as Russia’s new petty tyrant and Romanov emperor. In his short three-year rule, he reversed many of the reforms and policies of his mother, viewed the French Revolution as an invidious threat, restricted freedoms of speech and literature, and increased the powers of the hated secret police. His reign was marred by his ruthlessness and paranoia of virtually everyone around him and his misjudgments in diplomacy and international affairs. As a result, a mood of military mutiny developed, and many feared that, like England’s King George III, Paul was losing his mind. Surely, he was Russia’s most uncomfortable emperor, totally unsuited for power. Even his closest advisers came to believe that something drastic had to be done to save the motherland—a forced abduction, banishment, or worse. His son, Alexander, could then reign and rule as Russia’s regent, as George IV would do for many years in England.

If Alexander agreed to the plot to arrange his father’s banishment, he never consented, at least not explicitly, to the conspiracy that took his life. “All along he had truly, perhaps, naively, believed that a peaceful abdication was possible.”[6] A palace murder, however, was exactly what transpired when late on the night of 23 March 1801 in the supposed safety of his own chambers, Paul was cruelly bludgeoned to death by his own guards and honored advisers. The news given out to Russia was that he had died of natural causes, most likely of an apoplectic seizure. His wife, Maria Feodorovna, almost immediately blamed her son Alexander for the murder, though she later changed her mind as more details of the killing emerged. Alexander, however, was stunned by the tragedy and seemingly unaware of how far this deadly turn of events had gone. He came to blame himself, if not for killing his father, then for not saving his life. He soon began to torment himself for his father’s death and more particularly for the cruel manner in which he had been killed. Alexander was driven to moments of deep despair and anguish for being an unwitting accomplice in the affair. “It imposed upon him an ineffaceable stain,” wrote one of his more recent biographers, “and it could never be wiped from his soul. . . . It settled like a vulture on his conscience and paralyzed his best intentions and faculties from the beginning of his reign, . . . plung[ing] him into a somber reflection and mysticism, sometimes degenerating into superstition.”[7] “His mental tortures never ceased thereafter,” as another of his biographers phrased it. “As the months passed into years, with the murderers themselves unpunished, it became clear that Alexander was haunted, not by the crime he never witnessed, but by the conspiracy of which he had known too much and too little.”[8]

He was anointed Emperor Tsar Alexander I by the Metropolitan of the Russian Orthodox Church at elaborate ceremonies in St. Petersburg on 24 March 1801. The young and handsome twenty-three-year-old emperor, with Empress Elizabeth at his side, spoke the Orthodox Confession, prayed aloud for guidance and forgiveness (a most positive sign to the throngs of clergy attending the ceremony), and sought for the well-being of the Holy Russian Empire. Gathering in the streets of St. Petersburg, men and women bowed in reverence or thronged him eagerly to catch a passing glance as he rode by. Elegant as he was affable, the new tsar carried the hearts and hopes of Russia with him. Surely, they thought, he would usher in the needed reforms for which so many were praying.

Few reigns began so promisingly. Seeing himself as the protector of the weak and oppressed, Alexander in a single command restored the freedoms of the press and of the rights of assembly and travel, released thousands of political prisoners, and curtailed the excesses of the dreaded “secret chancellor,” or state police. He also founded the Society of Russian History and Antiquity, which began the collection of ancient documents and manuscripts that would prove helpful to later generations of scholars.

Surrounded by his “committee of friends,” consisting of gifted, liberal-minded young reformers who were encouraged by Thomas Jefferson and inspired by the 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man, Alexander also streamlined government bureaucracies and gave careful consideration to establishing a form of constitutional monarchy and an elected representative assembly. And, in the revolutionary spirit of the time, Alexander and his advisers likewise considered abolishing that most deadening of all Russian institutions—serfdom! Had it not been for the vested powers of the influential privileged classes—the nobility and the clergy—he would likely have gone much further.

Unfortunately, the tradition-bound, ritualistic, and overly conservative Russian Orthodox Church was never comfortable with the free-spirited religious nature of the new emperor. Since at least 1789, Russia had been experiencing a revival of Christian religion not seen in centuries. Taking many different forms, this rebirth of piety was “stimulated by a rejection of the decayed formation of official churches” and by “the excesses of rationalism and skepticism.”[9] Whether English evangelicalism, German Pietism, or simple English Quaker-style spirituality, there was at this auspicious time a widespread, genuine hunger for new modes of religious experience.

In Russia, despite the opposition of the church, mysticism had become very popular. Increasingly uncomfortable with dogmas, ancient creeds, and liturgical ritual, these Christian mystics sought the “internal church,” a kind of spiritual rebirth by which men lived in Christ and Christ in man, a true mystical union and communion with God.[10] Freemasonry—with its long-standing emphasis on brotherhood and equality, on secret oaths and sacred lodges, and on Christian service and virtuous living—became “a comforting social anchor” and religious expression for many. It would flourish all across Russia until it was eventually repressed in the religious retrenchments of the late 1820s.[11]

Above all, in this short-lived window of religious freedom and opportunity that existed from about 1790 to 1825, the Russian Bible Society virtually swept the country. Established in 1813 as an extension of the British Foreign Bible Society (see chapter 10), the Russian Bible Society was a favorite of Alexander; Golitzen (Golitsyn), his minister of Foreign Creeds; and even, at least initially, the Russian Orthodox Church. More than a mere mechanism for distributing the Bible into the homes of millions who had never before possessed scriptures in their home, the Russian Bible Society was an ambitious, enthusiastic, Christian crusade involving the energies of hundreds of thousands of loyal supporters in disseminating the Bible. In the repressive years that followed Alexander’s reign, as historian Judith Cohen Zacek has said, Russia “settled back into its age-old formalism, narrow-mindedness, and theological stagnation,” and in 1826 the Russian Bible Society was abolished, though not without leaving an indelible impression upon the Slavic soul.

Portrait of M. M. Speransky, by unknown artist.

Portrait of M. M. Speransky, by unknown artist.

Meanwhile, in 1807 Mikhail Speransky, one of the country’s most revered reformers, became Alexander’s governor-general, closest confidant, and financial adviser, a power behind the throne. Within only two years, Speransky became secretary of state and effectively prime minister of Russia. A deeply religious, highly intellectual personality with both conservative and progressive views, Speransky was a firm believer in the state’s active role in directing the progress of the nation while at the same time wishing to promote “the untrammeled activity and free enterprise of individuals.”[12] Speransky was a true agent for change. He proposed such far-sweeping liberal reforms as a limited constitutional monarchy, a system of much-improved education, the cautious reduction of serfdom, the establishment of luxury taxes on the rich, and entrance exams for potential civil servants. One of his most lasting achievements was to codify Russian law and to infuse into government bureaucracy a sense of the spiritual and of greater morality.[13]

Tragically for Russia and its future, Speransky’s jealous enemies successfully portrayed him as a traitor to Mother Russia and a defender of French political ideals and freedoms as the shadow of Napoléon loomed ever larger and more menacingly across Europe. Speransky’s tragic fall and dismissal in 1811 by a tsar who ever loved him but was too weak to sustain him marked the end of Alexander’s age of reform—it had been a sacrifice to the vested interests of selfish landowners, the nobility, and the church. Had Alexander possessed the strength of his own convictions, a less divided personality without the weaknesses of character that played into the hands of powerful detractors, his reign might have ended far more successfully than it did. Had he shown the courage to transform society as he once daringly set out to do, his reforms may well have saved Russia and the whole world from the bloody atrocities of the Russian Revolution and the scourge of Communism a century later.[14] So it is that the great door of history turns on such tiny human hinges.

A Tale of Two Emperors

By 1804 the insatiably ambitious and unstoppable Napoléon had already overrun Italy, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Spain, the Rhine states, the Duchy of Warsaw (Poland), Denmark, Norway, and much of Prussia and Austria. As we have seen previously, the emperor of the West had no desire to invade Russia then but instead sought to overpower Great Britain, one way or the other. Similarly, Alexander, the emperor of the East, had no desire to confront the French juggernaut. Only because of his previous alliances with Prussia and Austria, now staggering under the weight of Napoléon’s blows, was Alexander finally drawn into open warfare at Austerlitz (in present-day Czechoslovakia) in December 1805.

With a flair for the theatrical and a naive, exaggerated, and untested belief in his own abilities as a military commander, a bewildered Alexander overruled his top generals and rode to the front of the Russian armies against a far more experienced, savvy, and formidable opponent. With the combined Russian, Austrian, and Prussian lines divided too thinly at the center, Napoléon waited cat-like for the opportune moment to pounce. Constantine, Alexander’s brother, led a foolish cavalry charge in which he was almost killed. What Alexander hoped would have been a great victory soon turned into a murderous rout, with Alexander himself almost being captured. The Russian Army retreated, bruised but not broken. Napoléon once again carried the day, while a shattered Alexander, shedding tears of humiliation, retreated in disgrace to St. Petersburg. It was a cruel and bloody lesson in the heartless realities of war. Public reaction to Alexander’s bungling of the battle soon turned bitter and angry, and those who had once shouted his praises now jeered in derision. For months, as became his custom, Tsar Alexander turned inward and noncommunicative, full of remorse, self-condemnation, and regret.

In the meantime, Napoléon kept on coming, winning at Jena, Auerstadt, and Friedland in June 1807. With neither man wanting to take on the other at this time, Napoléon sued for a peace that Alexander was more than eager to accept. In their famous Treaty of Tilsit, signed on a raft in the middle of the Niemen River, the two men countersigned what essentially became a treaty of distrust, where each promised to leave the other alone—at least long enough for Napoléon to carve up Europe and Alexander to do the same with Turkey and the Ottoman Empire. Alexander agreed to join Napoléon’s continental embargo of Great Britain on the condition that Napoléon would let Alexander expand into Finland, Sweden, and Constantinople. Both agreed to divide Prussia between themselves. While Napoléon thought he was charming his Russian counterpart into believing he was Russia’s foremost ally, he never fully gauged Alexander’s political astuteness and unyielding loyalty to the motherland. The fact is, the two men never did understand one another—Napoléon underestimating Alexander’s resolve and Alexander overestimating Napoléon’s political savvy.

But the continental system proved ruinous to the Russian economy. And Napoléon’s excesses and brutality galvanized opposition in virtually every sphere and segment of Russian society. Despite his setbacks, Tsar Alexander was now regarded by serf and noble alike as Russia’s only true hope and the only force strong enough to counter the Corsican anti-Christ. An absolute frenzy of Russian patriotism and religious fervor swept over the land, destroying any attempts at reconciliation with France. When Napoléon and his Grande Armée attacked that fateful summer of 1812, never was Mother Russia more united against its advancing foe.

Psalm 91 was not the only scripture from the Bible to catch Alexander’s eye that forlorn day in St. Petersburg. Drawn to the eleventh chapter of the book of Daniel, he took courage and renewed determination to fight from the following passage:

And the king of the south shall be moved with choler, and shall come forth and fight with him, even with the king of the north: and he shall set forth a great multitude; but the multitude shall be given into his hand. . . .

For the king of the north shall return, and shall set forth a multitude greater than the former, and shall certainly come after certain years with a great army and with much riches. . . .

So the king of the north shall come, and cast up a mount, and take the most fenced cities: and the arms of the south shall not withstand, neither his chosen people, neither shall there be any strength to withstand. . . .

And at the time of the end shall the king of the south push at him: and the king of the north shall come against him like a whirlwind, with chariots, and with horsemen, and with many ships; and he shall enter into the countries, and shall overflow and pass over.

He shall enter into the glorious land, and many countries shall be overthrown. (Daniel 11:11, 13, 15, 40-41)

With help from the spiritual advisers and mystics about him, Alexander began to see himself as God’s divinely appointed agent to fulfill prophecy, especially after Napoléon’s occupation of the holy city of Moscow and the desecration of the Kremlin, the sacred center of Russia. No matter how one chooses to see it, there can be no disputing the fact that the Russian defeat of Napoléon’s Grande Armée, with the help of Russian “Generals January and February,” was nothing less than a remarkable campaign, a stunning, undeniable victory. Not content to stop at Poland or Prussia, Alexander and his Russian Army followed in close pursuit of the retreating Napoléon like a hound on the chase. After Leipzig and the Great Battle of Nations, one battle followed after another until finally Alexander rode triumphantly into Paris on 31 March 1814—the first foreign conqueror to enter Paris in four hundred years—stunning even his Austrian and British allies with the speed of his incredibly successful westward march.

But “Freedom’s Morning Star,” as Alexander came to be called, was not hell-bent on vengeance. How could he be, since he believed God had given him a victory? The fact was, Alexander truly admired Napoléon and thought seriously of creating a regency for Napoléon’s three-year-old son; however, working with the duplicitous French foreign minister, Talleyrand, who had served every French regime for the past twenty-five years, Alexander changed his mind. After signing the Treaty of Fontainebleau, which restored the Bourbon king Louis XVIII to the French throne, and exiling Napoléon to Elba, the charming Alexander enjoyed Paris’s famous night life, at one time dancing with none other than Marshal Michel Ney’s wife and even with Josephine herself, Napoléon’s first wife. Alexander insisted in the First Treaty of Paris that France be treated most leniently, because Napoléon, not France, had been his enemy. He did not even demand indemnities of France—the payment of reparations for the costs of war. France therefore retained many of her expanded borders and escaped without even paying reparations. In retrospect, one wonders what the wars had all been about.

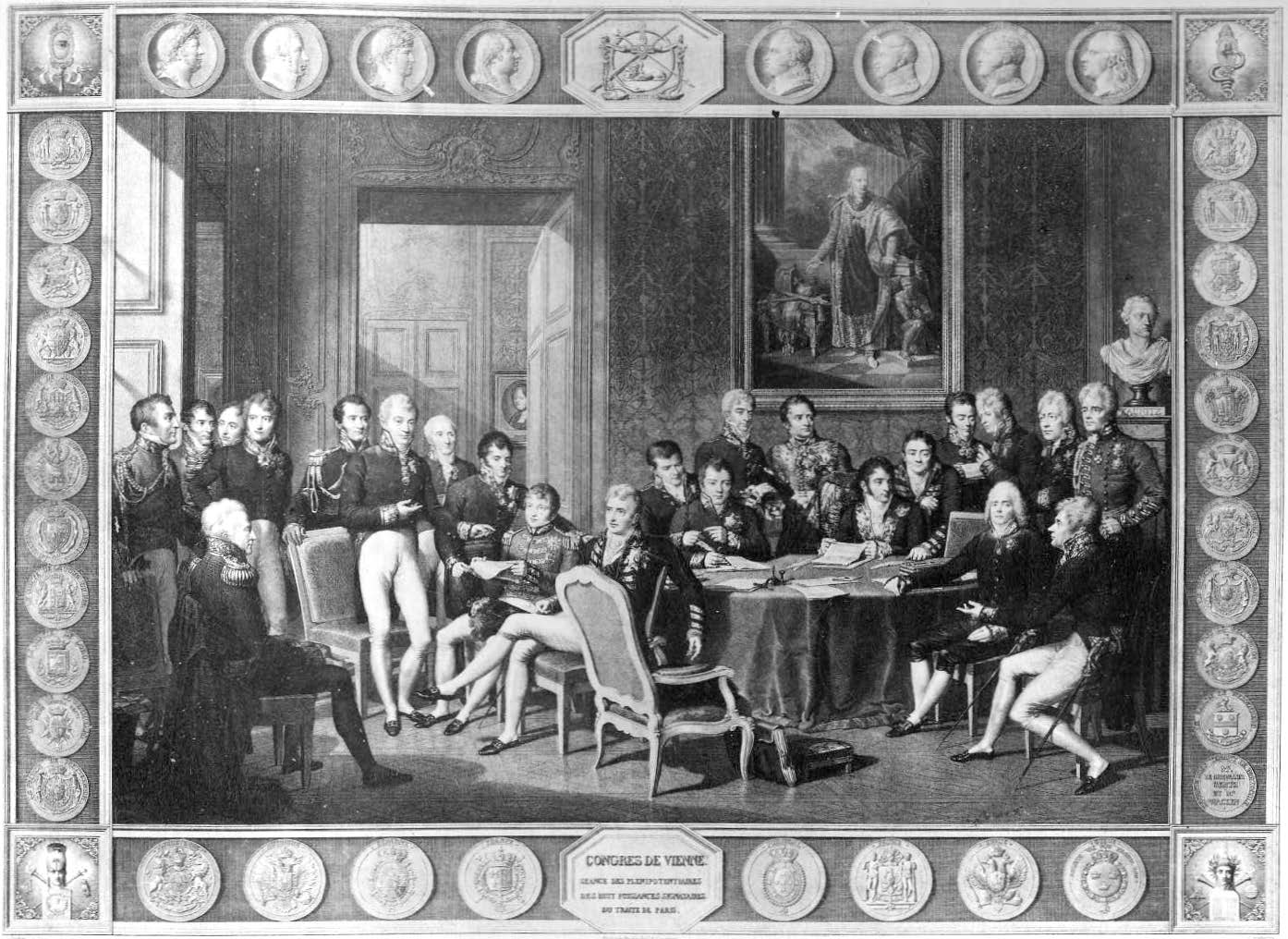

The Congress of Vienna

Such stupendous events as those described above—when emperors, armies, and millions of people were on the march, forever changing boundaries, perceptions, and nation states—inevitably required cool heads and diplomatic reasoning to bring new order out of war-torn chaos.

Alexander’s rapid march westward across Europe in the wake of his enemy’s rapidly receding armies and his eventual triumphal entry into Paris positioned the Russian emperor as the sole “arbiter of Europe’s destiny.”[15] Yet his victories worried many of his allies that he had gone much too far and much too fast. Forty-two-year-old Klemens von Metternich—Austria’s astute, calculating secretary of state from 1809 to 1848 and arguably the mastermind behind the eventual restructuring of postwar Europe—feared Russia with its standing army of almost one million men almost as much as he did France. Representing a composite state of diverse loyalties (Germans, Magyars, Slovaks, Poles, Slovenes, and Italians) whose borders on all sides could be easily overrun by enemy armies, Metternich feared that one empire was merely replacing the other. A supreme realist and a shrewd judge of human nature as well as of foreign affairs, the conservative Metternich distrusted Tsar Alexander’s enigmatic character, his vanity, and his religious, almost mystic motivations, choosing to see the Russian leader as an unstable visionary and dreamer. Thus, even before the fall of Paris, he was busily planning a congress of power to convene at his invitation in Vienna.

Meanwhile, the other architect of Europe’s future—Great Britain’s Irish-born Viscount Castlereagh, foreign secretary from 1812 to 1822—was as cumbersome and inarticulate as Metternich was smooth and eloquent. Icy and aloof, Castlereagh was nevertheless astute and immensely intelligent, and he signaled England’s intention to participate—indeed to take a leading role—in preventing the rise of Napoléon or anyone else like him from ever taking power again. An island nation defended by its formidable navy, England ambitioned to protect itself from future French invasions through the formations of strong alliances, to remain free from European entanglements, to preserve and extend its far-flung colonies through the formations of such alliances, and to gain wealth from overseas trade. The safeguard of its maritime power and prominence was England’s highest priority. Less concerned with far-away Russia, Castlereagh sought a new balance of powers to ensure a lasting peace.

Both Metternich and Castlereagh—along with Prussia’s Hardenberg, who was anxious to restore as much of the constantly overrun Prussia as he could—wanted to negotiate a European peace as soon as possible. Alexander, however, stubbornly and defiantly insisted on marching to Paris, believing that it was “his mission to destroy the Napoleonic state and then seek revelation of what was to take place.”[16]

In June 1814, in company with his sister Catherine, Alexander visited England, where he was thronged by vast and adoring crowds who hailed him as “the Christian conqueror who saved Europe.”[17] Given an honorary degree by Oxford University as “Liberator of Europe” and “Freedom’s Morning Star,” Alexander agreed not to use Russia’s entrenched military position to gain undue influence. Instead, he promised to negotiate with the other allied powers in formulating a lasting European peace—in other words, to go to Vienna.

The Congress of Vienna that opened 1 October 1814 and lasted the following seven months went down in history as the first, and certainly one of the most important, assemblies of world powers ever convened. Its purpose was multiple: to redraw the political map of Europe, to protect the autocratic rule of the great powers against the rise of future revolutions of the kind and scale of the French Revolution, to keep Napoléon from ever rising again, and above all, to establish a fair balance of powers in Europe that would ensure a lasting peace. Alexander hoped the conference would agree to one other action: a provision wherein the big four powers would form a Holy Alliance and a system of future congresses that, like the later League of Nations, would bring leaders of the great nations together to avert a further calamity like the one they had just witnessed.

Portrait of M. M. Speransky, by unknown artist.

Portrait of M. M. Speransky, by unknown artist.

Every European nation, sovereign state, principality, and power, small and great, that had any interest whatsoever in postwar Europe was invited. Thus, Vienna that winter of 1814-15 witnessed a glittering gaggle of kings and queens, prime ministers and potentates, emperors and empresses on a scale the civilized world had never before seen. Austria’s host emperor, Francis I, spent vast sums of money—some thirty million florins—lavishly dressing up the city and preparing it to host a hundred thousand people, providing a social life of banquets and balls, concerts and symphonies, festivals and festoons, and a night life of rustling gowns and squeaking shoes. Little wonder it has gone down in history as “le Congrès qui danse” (the dancing Congress)!

Even before they formally convened, the Great Four Powers—Great Britain, Austria, Russia, and Prussia—had secretly agreed among themselves to be the directing committee, running the show on their terms and to their own advantage. Lesser powers such as Spain, Portugal, Holland, and Sweden would be kept informed but take a much lesser role. Going into the Congress, the most immediate question was what to do with France, its place in postwar Europe, and more immediately, what position would its foreign minister, Talleyrand, be allowed to play in the negotiations.

At the risk of simplifying a most complex affair, the Congress of Vienna was a mixture of Alexander’s idealism, Metternich’s materialism, and Castlereagh’s pragmatism. Russia, with a population of forty-three million, wanted all of Poland and access to the Mediterranean Sea. Prussia, with its ten million, wanted more land on the east and on the west to better defend itself. Great Britain, with its eighteen million, eyed the port of Antwerp and wanted France out of Belgium. Austria, with its eight million, sought much of northern Italy and, above all, a political equilibrium where no one power could overrule Austria or the rest of Europe. The emphasis would not be on punishing France but rather on establishing a balance of force. If lands—and after all, land represented people, industry, and money—could be properly distributed to the winning sides, and if a new balance of power could be implemented, then perhaps the Congress might be successful. As for France, Talleyrand quietly maneuvered behind the scenes to minimize French losses and to regain the country’s status as a major power.

The Congress was also as much concerned about turning back the clock as it was in realigning the future boundaries of Europe. The peacemakers of 1815 were, as Tim Chapman has argued, “backward looking and conservative”—wanting to put the genie of revolution back into the bottle of autocratic rule.[18] However, those key ideals of the French Revolution—liberty, equality, and fraternity—along with belief in a constitutional monarch, representative government, and such basic civil rights as freedom of religion and speech would not be easy to contain or resist, especially in those countries closest to France and longest occupied. Prussia, the Rhineland, the Low Countries, and the northern Italian states had been deeply influenced by such French reforms as the abolition of serfdom, curtailing the power of the trade guilds, and improving education. While the new power brokers “absolutely opposed the idea of countries being ruled without a hereditary ruling family,”[19] they found some of Napoléon’s reforms impossible to resist. As one scholar has argued, “The Napoleonic Codes were, for the most part, retained, and the rulers realized that the limited progress that had been achieved under the French could not be undone.”[20] If a new age of nationalism was not yet the issue, a new era of liberalism certainly was. While Austria sought for the authority to intervene in other nation-states’ affairs in order to resist revolutionary impulses, Great Britain was more or less content to let each nation do as it deemed best, unless of course its own commercial interests were at stake.

The peculiar nature of the Congress of Vienna did not agree with Alexander but was tailor-made to fit Metternich’s manipulative style of back-room diplomacy. Accustomed to poring over copious memoranda and to taking the lead in conferences, Alexander was ill-prepared for corridor communications, sideline conversations, and dealings made on the sly at the symphony or in the parlor. A constant beat of nightlife and carefully arranged meetings with mistresses sank the whole affair almost to “the level of a cheap farce.”[21]

But a farce it was not. The Congress of Vienna was far more than a meeting of diplomats; rather, it was a gathering of nations and of national and cultural expressions, something akin to a carnival of nations. And women played far more than a passive role in this, colorful consortium of political, cultural, and national interests. During the Congress, “it was the ladies as mavens of society who took the lead and set the tone for sociability in general and political sociability in particular, providing informal political contacts and exchanges.” [22] Friendly and informal salon gatherings—where representatives and diplomats learned of each other’s favorite foods, music, literature, and customs of the various cultures and nations—probably did more to lessen tensions and increase understandings between delegates than anything else. In short, social gatherings were highly significant to bridge-building between peoples and to the ultimate success of the Congress.

Likewise, such gatherings lessened religious misunderstandings and prejudices. Brian Vick, in his new study of the Congress, makes it clear that religion and religious freedom and toleration were hot topics of discussion, especially in light of the fact that new national boundaries meant millions of people were now living under new confessionals of faith. “The idea of protecting the rights of religious minorities”—though a very prickly issue—“found much support at the Congress.”[23]

Throughout the Congress, Metternich clearly knew what he was doing and patiently played his hand. At the outset, he felt Alexander held the upper hand, with his armies still occupying most of Europe. Thus, he purposely dallied and delayed to wear down Alexander’s patience. The two men quite honestly despised one another and never met in open conference or spoke with each other until the very last day of the conference. As one described, “Le Congrès danse, mais il ne marche pas” (The Congress dances, but it doesn’t walk/work).[24]

The negotiations stalemated and nearly ruptured over Poland. Prussia demanded the return of its lost eastern provinces, while Alexander insisted on retaining what Russia had overrun. Sensing that France—the conquered, ostracized power—was the key to achieving a lasting balance, Metternich feigned one illness after another to buy time and public support. And while the British cabinet signaled little interest in repositioning France as an equal power, its clever foreign minister, Lord Castlereagh, quietly maneuvered for France to play a leading role, fully realizing his position would not play well back in London.

The fact was that both Metternich and Castlereagh realized that this was a conference less designed to punish France and more designed to establish a lasting European peace. To achieve a stable future, France had to be included with a strong voice and as an equal power. Sensing such determination, Prussia threatened a new war and almost pulled out of Vienna, yet reluctantly realized it had little choice but to compromise. A new alliance, with France now included, was ultimately signed 3 January 1815, with the Big Four becoming the Big Five.

The Prophetess

Two widely different events broke the logjam of continuing intrigue and stalemate: one close at hand, the other hundreds of miles away. In one of those life-changing moments, like that of the Bible falling on the palace floor three years before, a determined old woman banged so loud and so long on Alexander’s castle door in Heilbronn late one night during a recess in the conference that his imperial guards finally had to allow her entrance. Believing God had sent a messenger to him (she had sent him letters well in advance), Alexander allowed the woman—Baroness Julie von Krüdener—into his chambers. In short order, this Livonian prophetess, a widow of a Russian diplomat and an evangelical Protestant who had earlier taken up spiritualism, begged his pardon for her intrusion. She then, however, scolded the emperor for his sinful ways and called upon him to repent and surrender his soul to God and to accept the formidable destiny and divine calling God had given him. She went on to call him to surrender his soul to Christ and to fulfill the God-given, predestined mission she had been sent to remind him of—to establish a Christ-centered peace in Europe and, as “the chosen one of the Lord,” to lead God’s people to the promised land. Impressed by her boldness and stung by his own punishing conscience for his many past sins, Alexander listened intently to every word this haggard, mission-driven Joan of Arc had to say. She chastised him as no one had ever done, but because of the peace she brought to his hankering, troubled soul, he instantly fell under her will as his spiritual guide, conscience, and personal prophet.

In what came to be a bizarre relationship that lasted the year, Baroness Krüdener became his trusted spiritual adviser who would later claim for herself many of his accomplishments. Believing that Alexander was the “one upon whom the Lord has conferred a much greater power than the world recognizes,” she stroked his ego while calling him to repentance.[25] Because she was hated by the Russian Orthodox Church, Alexander felt compelled to banish her in 1822.

Baroness Barbara Juliane von Krüdener (1764-1824), by unknown artist.

Baroness Barbara Juliane von Krüdener (1764-1824), by unknown artist.

Having been reminded of the divine calling he had long believed he owned, Alexander returned to Vienna with renewed energy, determined to change his approach with Metternich and the Congress. Preferring now to play the role of a benevolent overseer and of the more compromising superpower, he softened his position on Poland and signaled his intent to negotiate in return for the realization of his new Holy Alliance.

Meanwhile, on 7 March 1815, Vienna heard the seemingly impossible news that Napoléon had somehow escaped Elba and was then on his way back to France. No one knew then what kind of reception he would receive, but Metternich rightly judged he would head straight for Paris and for power. The allies immediately pledged an army between eight hundred thousand and one million men. With most of the Russian army still stationed in Poland, everyone agreed that Wellington would be the supreme commander of the British, Prussian, and other nearby armies to join with Alexander’s overwhelming force and put down the revived French threat once and for all. “It is for you to save the world again,” said Alexander to Wellington.[26] And as we have already seen, three months later Napoléon lost at Waterloo, outmanned and outgunned by superior allied forces.

The height of Krüdener’s influence over Alexander came after Waterloo when she accompanied Alexander to Paris, where the allied powers signed the Second Treaty of Paris. On 11 September 1815, dressed in a blue serge dress and straw hat, she stood beside the Russian emperor as they reviewed an immense military parade of 150 squadrons of cavalry, over 100 battalions of infantry, and 600-plus pieces of artillery march through the town of Vertus, near Paris. After the heavy march had passed, 150,000 Russian troops assembled in seven gigantic squares and kneeled in unison around seven large altars: “the mystic number of the Apocalypse,” in reference to John the Revelator’s seven churches. Then the bishops and priests celebrated mass according to the Russian Orthodox liturgy and offered thanksgiving prayers for their recent victory over Napoléon. Convinced that he was witnessing the fulfillment of prophecies from the book of Revelation and that the “Christian Russian forces were equated with the new Israel,”[27] Alexander, with the baroness beside him, moved in procession from altar to altar. Filled with love for his enemy, “in tears, at the foot of the cross, [he] prayed with fervor that France might be saved.” For Alexander, it was “the most beautiful day in his life.”[28] But for others, like Castlereagh, they worried about the deeply religious spirit that had come over him, while Metternich and Emperor Francis I thought him mad.

Both Alexander and Krüdener and those other religious mystics of the time saw in this magnificent occasion and grandiose spectacle not only a fulfillment of biblical prophecy but also the herald of the latter days. As the German mystic Eckartshausen put it, “That time when the great veil concealing the Holy of Holies shall be drawn back, the ushering in of the last times on earth before Christ’s Second Coming.”[29] As Eckartshausen and many other mystics believed, the last days truly began with the first decades of the nineteenth century.

It was shortly thereafter, while in Paris, that Alexander presented his counterparts with his Holy Alliance, a “Sacred treaty,” “a new Dispensation of Holy Writ,” a moral statement sent from God to bind all Europe’s rulers in a “union of virtue, peace, forgiveness, and Christian brotherhood.”[30] Though influenced by Krüdener, the document was of Alexander’s own making—a reflection of years of religious thinking. Long on virtues and short on specifics, the Holy Alliance was not a treaty per se but a declaration of policy, a promise of a future policy. All but the pope, the leaders of Great Britain, and the sultan of Turkey signed it on 26 September 1815, not because they supported it in principle but because it held no binding power over them. Castlereagh called it “a piece of sublime nonsense” and Metternich “a loud-sounding nothing.”[31] As Henry A. Kissinger argued, Castlereagh and Metternich, whatever their differences, “sought a world of intermeshing nuance, Alexander one of immediate perfection.”[32] The one strong suit of the treaty, and perhaps its lasting significance, was its binding invitation to all the powers to meet regularly thereafter whenever world peace was threatened. Believing that he had fulfilled his divine appointment, Alexander seemed to have lost interest and delegated the details of further negotiations with the allies to his ministers and ambassadors.

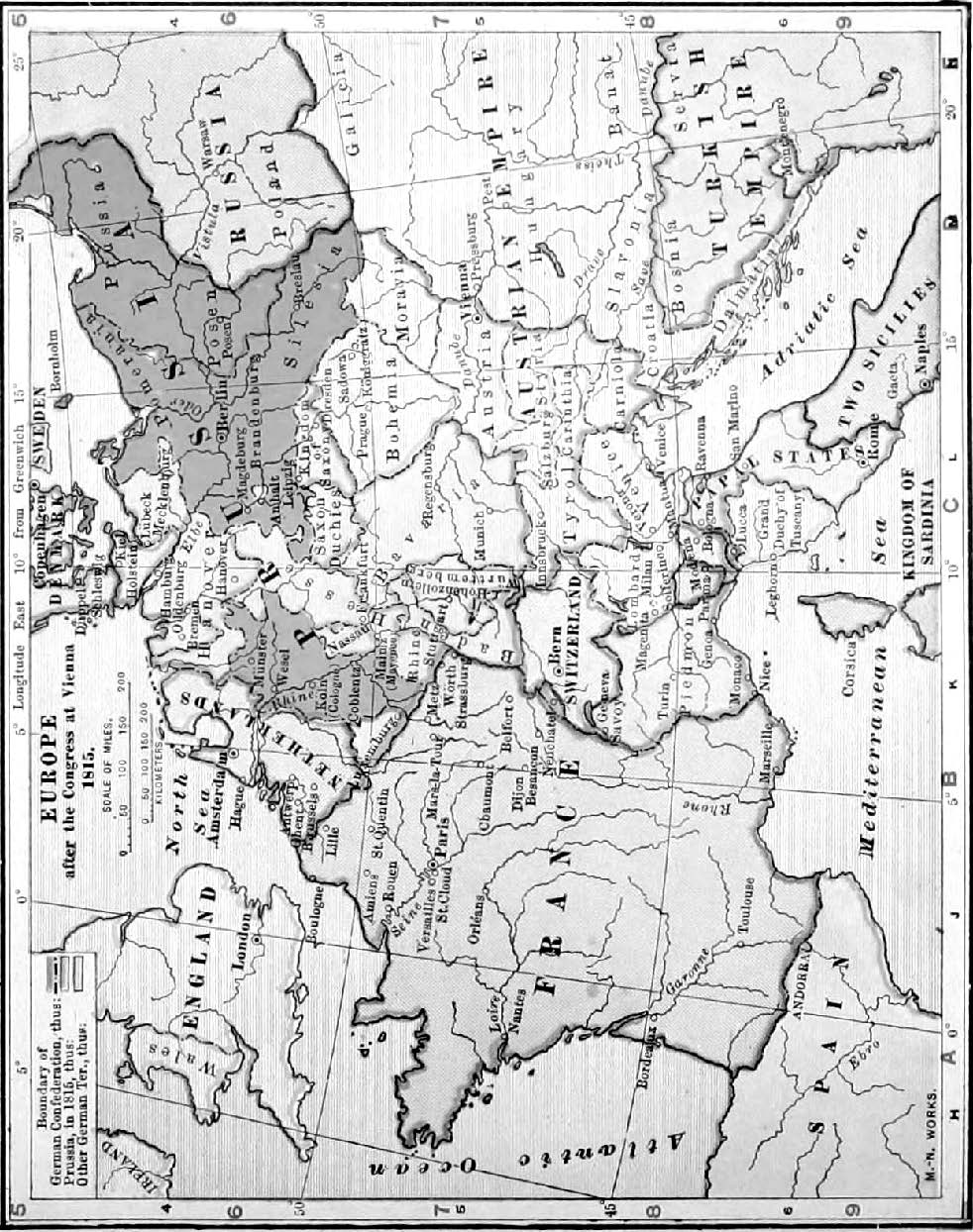

The negotiations at Vienna accelerated during Napoléon’s One Hundred Days that ended with his defeat at Waterloo. With the sixty-year-old, notoriously immoral Talleyrand (Napoleon had once called him “filth in silk stockings”) at the table, no longer representing Napoléon but the French Bourbon government, the Big Five powers hammered out the terms of a final agreement in what clearly was “an uneasy compromise.”[33] Alexander acquiesced and contented himself with the Duchy of Warsaw and eastern Poland, promising the Poles something the Russian people themselves would not be allowed—a constitutional monarchy and a representative government (though in truth Russia would rule Poland with an iron hand). Austria retained Hapsburg rule and acquired much of northern Italy, including dependent dynasties in Parma and Tuscany. Great Britain held on to Ireland, Holland, the free part of Antwerp (Belgium), and of most importance—all its colonies. Prussia, in many ways the winner of Vienna, obtained much of Saxony, Swedish Pomerania, much of the Rhineland, and the Duchy of Westphalia. A new German Confederation, a loose union of sovereign princes, came into being and reduced the number of states and free cities from 350 to 16—a giant step forward toward the ultimate creation of modern Germany. France escaped without being reduced in size, but several buffer states—Bavaria, Piedmont, Holland, and the Rhineland, the so-called “cordon sanitaire”—were placed between it and the other great powers.[34]

Europe after the Congress at Vienna 1815. From The New International Encyclopædia, vol. 7, facing p. 290 (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1903).

Europe after the Congress at Vienna 1815. From The New International Encyclopædia, vol. 7, facing p. 290 (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1903).

The Final Acts of Vienna were ratified 9 June 1815. As Kissinger argued, Vienna, for all its intrigue, social glitter, immorality, and corridor diplomacies, created a new European order, a successful balance of powers, and a lasting, “just equilibrium.” Not “a fortunate accident” but a deliberate effort, “there existed within the new international order no power so dissatisfied that it did not prefer to seek its remedy within the framework of the Vienna settlement rather than in overturning it.”[35]

In the Second Treaty of Paris, signed after Waterloo, the allies were furious with Napoléon and, had it not been for Castlereagh’s astute diplomacy, would have tried to dismember France altogether. Napoléon was banished to St. Helena, and Marshal Ney, “the bravest of the brave,” was executed for supporting Napoléon’s return to power. Although more punitive terms were placed on France—slightly reduced territories, fewer overseas colonies, a smaller standing army, the forced return of art seized abroad, and an indemnity of seven hundred million francs (a sum France paid back in just three years)—this second peace treaty was surprisingly lenient in its treatment of France, a recognition that the enemy had not been the country but rather its emperor. If it lacked the magnanimity of the first Peace of Paris, “it was nevertheless not so severe as to turn France into a permanently dissatisfied power.”[36] Thus out of Paris came the two instruments that would guide Europe for several decades—the Quadruple Alliance and the Holy Alliance: “the hope for a Europe united by good faith and the quest for a moral consensus, [and] the political and the ethical expressions of the equilibrium.”[37]

The peace that followed the Congress of Vienna and its resultant treaties and systems of congresses (Aix-la-Chapelle, Carlsbad, Trappau, and Laibach) would last the better part of a century. Save for the pending wars of independence in South and Latin America, the American Civil War (1861-65), Bismarck’s Franco-Prussian War and hostilities of the 1870s, and scattered, various revolutions, the modern world sat upon a relatively stable course of peace. Thus unlike the Versailles Treaty of 1918 a century later, which, while ending the terrible conflict of the First World War, nevertheless gave rise to the Second World War a generation later because of its harsh and punitive demands upon Germany, the skillful, forward-looking diplomats of 1815 set in place a lasting, fair, international peace.

This ensuing peace engineered by the Congress of Vienna and the rising spirit of religious freedoms allowed for the expansion of religious missionary work throughout Europe and, indeed, the world, on a scale perhaps unseen before. Certainly, for missionary-minded religions such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the relative stability of world politics, the guarantee of peace, and increased tolerance for religious diversity were indispensable to their successful missionary efforts in the mid-to-late nineteenth century and lasting well into the second decade of the twentieth.

And while Alexander’s Holy Alliance, like Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations a century later, was long on dreams and ideals but short on specifics and binding contracts, it contributed nevertheless to fostering a spirit of future, ongoing negotiation and compromise. As World War II historian O. J. Frederickson has concluded, Alexander’s efforts, despite all the scorn and ridicule heaped on them, were “faltering steps toward a lofty goal.” It may well be that “Alexander will go down in history not as the victor over Napoléon but as the far-sighted initiator and champion of the World Federation which was finally achieved after World War II.”[38] So it was that the years which followed—the very age of our study—have gone down as an era of negotiated peace.

In Search of Peace

Although Alexander helped secure a lasting European peace, he never found peace for himself. The final decade of his life was marred by bouts of severe depression, aimless and excessive travels, profound disappointments, and personal frustrations. A reign that had begun so promisingly with its anticipation of change and needed liberal reform ended in despair and a hint of mystery that remains intriguing the present day. Europe’s widely acclaimed “Liberator” never escaped the chains of his own personal bondage.

For all of Krüdener’s efforts at saving his soul and for all the praise Mother Russia bestowed upon its favorite son, Alexander was an unhappy wanderer. He seemed to lose interest at a critical moment of his life and, instead of heading home directly to pomp and glory, he dallied all the way back to Russia, spending a week here or two weeks there. Clearly bored with life and possibly suffering from venereal disease, he seemed to be a man without home or hope, no longer wanting to govern, more inclined to run and hide than to take the helm. At one point in late 1812, he even hinted at abdication: “The throne is not my vocation, and if I were able to change my condition I would do it willingly.”[39]

Consequently, he let others do what he should have done. The efficient yet brutal guardian of feudal Russia—General Alexai Arakcheyev—soon took over the daily matters of government business. The very opposite of the more enlightened Speransky in outlook and personality, Arakcheyev was, as one called him, as “industrious as an ant, venomous as a tarantula,” turning back those impulses of reform that top Russian Army officials had first tasted in “free-thinking Europe.” There they had seen the enemy, and the enemy turned out to be not all that bad. In other words, “serfdom was not necessary to national prosperity,” and a constitutional government, a free press, and an open society were hallmarks of the new West.[40] Pushkin and a host of other hopeful Russian intellectuals and activists soon became disillusioned at Alexander’s failure to inspire on the one hand and Arakcheyev’s repressive measures on the other.

Arakcheyev’s repressive influence on domestic policies was most extensive during Alexander’s final decade. He organized a highly unpopular system of military colonies, enhanced the powers of the secret police, suppressed the intelligentsia, and with unnecessary force and brutality put down even the hint of riots and revolt (for example, the Decembrist revolt). While Alexander did encourage the promotion of the Russian Bible Society and the expansion of Russian Freemasonry, he never displayed the kind of hands-on, superintending style of leadership so many liberals yearned to see in Russia. Ever the idealist, he was always outmaneuvered by the materialists and those who resisted real change.

One of his most poignant failures and personal disappointments came with the Greek insurrections of 1821. Tailor-made for Russian intervention, the Christian Greek revolt, led by the Russian Orthodox Alexander Ypsilanti, a former Russian general, aimed at putting down the inhuman, barbaric dominance of the aging Ottoman Empire and the Turkish sultan’s control and at making an independent Greek state that was Christian and free. At the critical moment, Metternich persuaded Alexander not to interfere, though he himself had intervened all over Italy to put down similar revolutionary stirrings. While eventually Great Britain intervened in 1826-27 and supported the successful Greek war of independence and the establishment of a semi-independent state, Alexander’s dallying cost the lives of thousands. Ever after, Alexander blamed himself for his failure to take leadership in a cause he felt was right.

Delving even more deeply into mysticism, scripture study, and soul-searching, Alexander was a tormented man trying to escape himself. Although Alexander’s religious quest has been seen by some as a pose, there can be “no question of his sincerity; he prayed so long and often that his knees became calloused.”[41] His father’s murder cast a shadow that followed him over the vast steppes and mountain ranges of Russia. When his recently married sister, Catherine, died in January 1819 at the age of thirty, Alexander blamed her death on his sins. When his daughter, Maria, born of his early mistress Sophia, died at eighteen, it was to him a crushing blow, and he once again blamed himself—this time on his earlier immoralities. And when St. Petersburg was flooded in 1824 by the rising spring run-offs from the Baltic Sea, which resulted in the loss of many lives, he again reproached himself for inciting the wrath of God. And while it is true that he and his long-suffering wife, Elizabeth, rediscovered one another in a marriage of true friendship, Alexander never found lasting peace at home.

Finally, when his wife took sick with tuberculosis and a high fever in 1820, he moved the entire royal household from the damp and dismal climate of St. Petersburg to Toganrog, a city on the Azov far to the south. There, he contracted a fever and died 1 December 1825 at age forty-seven. Elizabeth followed him to the grave just six months later. His brother Nicholas (Alexander and Elizabeth never had a son) was more like their father than Alexander was. He outmaneuvered his brother Constantine to the throne, where followed thirty years of reactionary rule—“autocracy, orthodoxy, and nationality”—setting the country back a century.[42]

Today the location of Alexander’s body, which was thrice exhumed, is unknown, leading some to speculate that Alexander feigned his death to secretly abdicate and become a wandering prophet and monastic—Feodor Kuzmich—who would live on in Siberia for another thirty years.[43] While the truth is more likely that he died as emperor and was buried in some unknown tomb in southern Russia, Alexander’s death remains a mystery.

The great defender of Russia, liberator of Europe, self-proclaimed fulfillment of God’s prophecies, and king of the North returned from whence he came. Ever tormented by his past sins, he never found peace. One raised to rule, he sank into obscurity, a tragic figure who never really knew himself. A reformer early on, he gradually succumbed to his passion for order and paternalism. Although he saved Russia at one moment, he failed it at another. Yet, to his lasting credit, he overcame the conqueror. Working with those other men of Vienna—most notably Metternich and Castlereagh—Alexander hammered out a just peace, a Holy Alliance, that transcended themselves and their combined abilities and would endure for a century.

Notes

[1] Troubetzkoy, Imperial Legend, 105. See also Zorin, “‘Star of the East,’” 317. Alexander himself recorded: “I read the Psalms, which again and again gave me new courage to withstand the dark hours of the trial sent to me, I was sure of this, from above. I read in the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel; and I knew that I would withstand the hour of tribulation. I had not thought much of religion in previous years, but now, having reached the depth of despair and not knowing what would happen next, I had not other support or comfort than religion. The God of the Old Testament prophets was also my God.” Klimenko, Notes of Alexander I, 196.

[2] Troubetzkoy, Imperial Legend, 106.

[3] Troubetzkoy, Imperial Legend, 62.

[4] Alan Palmer, Alexander I, xvii.

[5] Troubetzkoy, Imperial Legend, 65. François-René Chateaubriand, French author and diplomat, once said of him, he “had a strong soul and a weak character” (65).

[6] Troubetzkoy, Imperial Legend, 57.

[7] Klimenko, Tsar Alexander I, 85.

[8] Palmer, Alexander I, 46.

[9] Zacek, “Russian Bible Society,” 418.

[10] Zacek, “Russian Bible Society,” 422.

[11] Smith, Working the Rough Stone, 177. One reason for the repression of the Freemasons was the suspicion that they fostered a spirit of revolution.

[12] Raeff, Michael Speransky, 306. In his political biography of Speransky, Raeff argues for a much more cautious, more conservative, reformer than do other students of Speransky. Nevertheless, even he concludes that despite his weaknesses of character and mystical personality, Speransky “helped to bring about a fundamental break with the past” and “brought order, lawfulness and stability into government machinery” (366).

[13] Raeff, Speransky, 362.

[14] Palmer, Alexander I, 87.

[15] Palmer, Alexander I, 286.

[16] Palmer, Alexander I, 272.

[17] Palmer, Alexander I, 290.

[18] Chapman, Congress of Vienna, 2.

[19] Chapman, Congress of Vienna, 15.

[20] Shinn, Italy, 24.

[21] Palmer, Alexander I, 309.

[22] Vick, Congress of Vienna, 14.

[23] Vick, Congress of Vienna, 162.

[24] Kissinger, World Restored, 160.

[25] Palmer, Alexander I, 310,. Krüdener’s influence on Russia’s leader has long been debated by historians and biographers alike. Some insist she was a dominating, mystical force who changed history forever; others prefer to see her as a mere confirmer of Alexander’s own deep religious convictions. Alan Palmer may be as accurate in his evaluations as any other scholar in his saying, “There remains in Julie’s exaltations and Alexander’s agonies of the soul a passionately compulsive power of conviction, . . . a genuine attempt to rend the veil of mortality and achieve a state of mind whence would emerge . . . Revelation.”

[26] Palmer, Alexander I, 322.

[27] Zorin, “‘Star of the East,’” 327.

[28] Palmer, Alexander I, 333.

[29] As cited in Zorin, “‘Star of the East,’” 327.

[30] Palmer, Alexander I, 334.

[31] Kissinger, World Restored, 189.

[32] Kissinger, World Restored, 187.

[33] Vick, Congress of Vienna, 240.

[34] Chapman, Congress of Vienna, 41, see map. Despite his brilliance as a compelling negotiator and superb strategist, Talleyrand was far from master of the Vienna conference. His “actions were always too precisely attuned to the dominant mood” for him to have played the lead role. Kissinger, World Restored, 136. Yet it must be admitted, the sly fox defended the interests of France superbly well.

[35] Kissinger, World Restored, 173.

[36] Kissinger, World Restored, 184.

[37] Kissinger, World Restored, 190. The Quadruple Alliance of Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Great Britain was signed 15 November 1815 and claimed the right to interfere with French internal affairs if further revolutions broke out.

[38] Frederickson, “Alexander I and His League to End Wars,” 22.

[39] McConnell, Tsar Alexander I, 179.

[40] McConnell, Tsar Alexander I, 169.

[41] McConnell, Tsar Alexander I, 177.

[42] McConnell, Tsar Alexander I, 200.

[43] For a further discussion of this debate, see Klimenko, Tsar Alexander I, 7-21.